From his closet of sneakers and various boots, Billy picks a pair to cultivate his artistic persona. In his first few shifts, he notices that while everyone working with him gives off confidence, they’re all wearing these clunky, black clogs that look like contoured bricks. Maybe there’s a reason behind why everyone else sports these bulbous monstrosities, but he doesn’t dwell on that for long. Billy makes it through his first few shifts just fine, and every time he looks down at his own boots he feels like he’s hacked the fashion-deaf shoe epidemic that has befallen his establishment. He looks great, he feels cool, and the last thing he’s going to do is spend his hard-earned money on clogs. During a shift, the restaurant’s bartender looks at him and goes, “Nice shoes, man.” The delivery feels a bit sarcastic, but Billy pays that no mind.

Billy settles into a rhythm after the first few weeks. He’s getting great tips, learning the menu well, and loves having full days off to focus on painting. Everything seems to be going smoothly. Well, almost everything. The morning after waiting tables, Billy wakes up with aches and pains in his feet. Moving around on his days off begins to feel like he worked his shifts with olive pits and lemon seeds shoved under the arches of his boots. Errands, dates, and workouts emphasize the soreness. Without the adrenaline of a dinner rush coursing through his body, he struggles to stay on his feet. The sarcastic bartender notices him bent over in the break room one day and points to her feet where two clogs rest in comfortable ugliness. “These things fix everything. You should get some,” she says. Billy laughs at the suggestion, but inside? The rage is bubbling. Buying clogs would mean a departure from the whole demeanor he’s set out to achieve; he couldn’t be this artsy dude who waits tables wearing clogs. Still, something inside him starts to agree with the bartender. Maybe he can’t work this job without giving up stylish footwear . . . The mere thought drives him mad, and he spends his next handful of shifts thumping around the restaurant, masking his frustration as the balls of his feet beg for cushioning and his friendly spirit dissipates in response to the pain. Billy’s pissed. He goes online one night just to see how much a pair of clogs would cost him, but slams his computer the minute the elf shoes pop up on his screen. Too ugly. Not happening.

After a particularly painful shift, Billy is sure that his boots can’t hold him throughout eight hours of service. His tips are dipping thanks to his darkened mood, and he can barely get anything on the canvas during his days off. He buys some black shoelaces and threads them through a pair of black sneakers he has in his closet, hoping the switch will answer his problems. It doesn’t. Billy now hobbles through his dinner shifts, switching which foot to put weight on every hour in an attempt to manage the searing pain radiating from his feet. Every night he falls into his bed and opens his computer to the tab where the clogs have been waiting. “What will people think of me if I get these?” he mutters to himself, surfing multiple sites selling the same black bricks. “What will I think of myself?” He considers a compromise: buying them and only wearing them one night out of the week, a night where he’s unlikely to serve a large amount of artsy, edgy diners who may laugh at his shoes. No, he couldn’t. Instead, he tries switching off from boots to sneakers to these dark leather loafers he thrifted a while back, but nothing works. The physical toll starts to outweigh the shame of succumbing to Big Clog. One dark afternoon, with his feet resting in bowls of ice, he opens that tab back up and clicks on the cheapest pair of clogs he can find. Across the screen flashes the dooming words: “Thank you for your Purchase!”

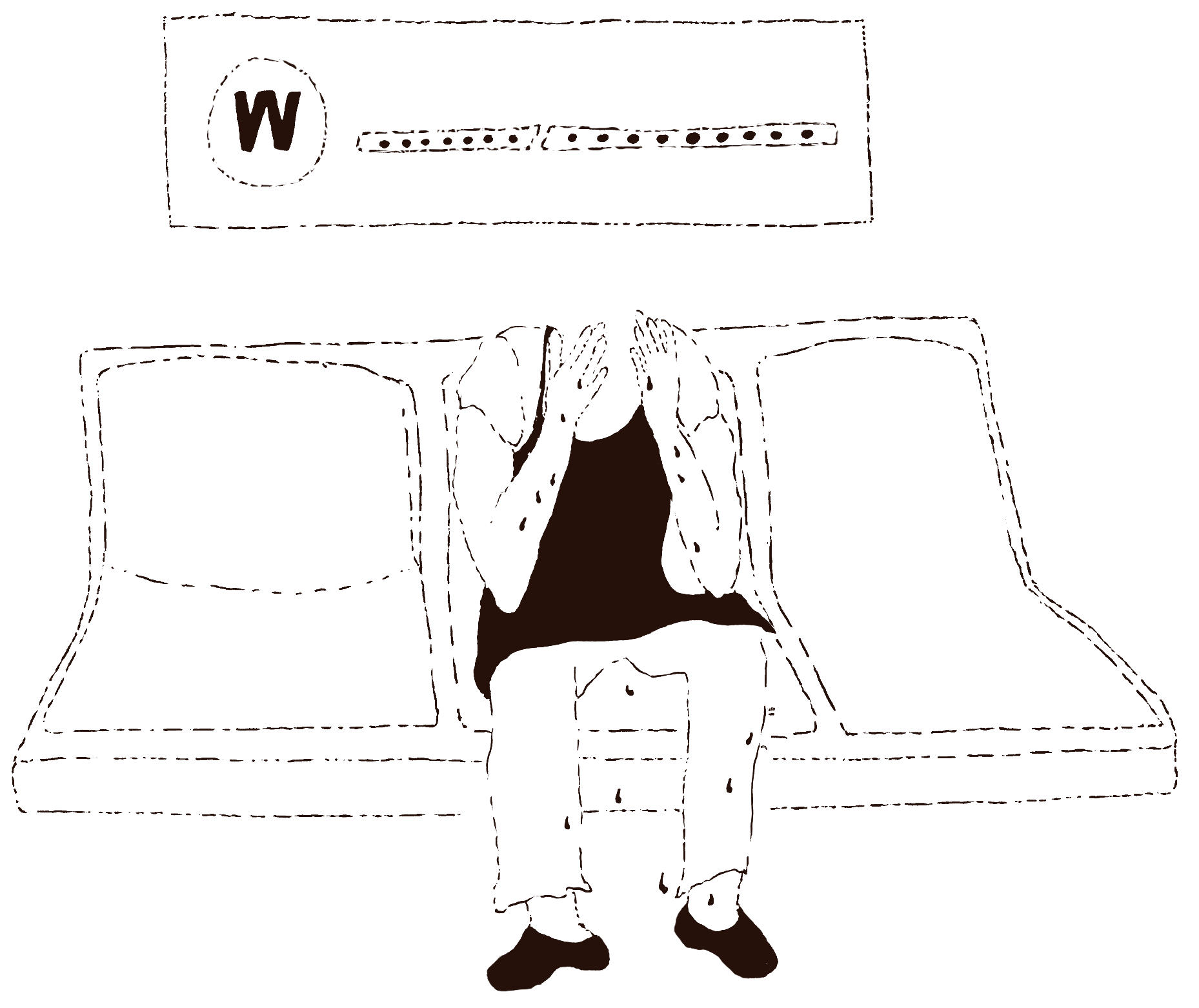

The clogs arrive, and Billy can hardly believe it. He feels defeated even having the pair in his apartment. He promises himself they are only for emergencies. Just to make sure they fit, he puts on a pair of socks and slips his aching, blistered toes inside. Butter would have felt sharper. Pillows couldn't compare. He stands up and months of pain subside instantly. Audibly exhaling, Billy realizes why everyone at his job —why nearly every waiter he’s ever seen, now that he thinks about it —wears these things. Stepping around his apartment, he feels like he’s walking on air. Passing his mirror, he catches a glimpse of himself and the beautiful sensation fades to black. Here he stands, a New York City artist with enough creative potential to fill every canvas he can get his hands on, wearing kitchen clogs. It’s too much. He slumps to the floor in weighted despair. That night, his dreams are plagued by nightmares of seeing his ex-girlfriend on the subway or running into a gallery curator while wearing his new shoes. He wakes in a cold sweat, shaking with desperation for another option, but he knows there’s only one way forward.

The first few shifts Billy works in his clogs feel like a breath of fresh air. He’s light on his feet and smiles at his tables throughout the entirety of his night. His clogs carry him in a way his cargos could never, and his days off are filled with pain-free energy; he’s even painting with brighter colors. Every hour or so, he glances down at his feet and remembers the days he wouldn’t even consider such a footwear selection. The first full week wearing clogs felt like a funeral — the death of a desired charisma, the ending of an artsy endeavor, but for comfort’s sake he chalks that up to dramatics. He now joins his clog-wearing coworkers with each shift. While he may not feel like the coolest kid in the East Village, he very well may be the comfiest. That’s a truth he’s willing to hold.

After six months waiting tables, developing his presence in art shows, and growing his community in the city, Billy’s manager asks him to train a new waitress. The girl is a dancer living in Brooklyn who needs more cash to afford ballet classes. She walks in on her first day with the same attempted swagger Billy had long ago: clean apron, slicked back hair, ironed shirt, and — of course — heeled black boots. Billy shows her around the restaurant, but once they have a minute to talk, he glances down at his clogs beside the shoes that are about to make his new coworker rethink everything. “Nice shoes.”

This is a story about Billy, but really, it’s one about all of us. Changing our ways to take on new challenges, leaving behind what we knew, never comes easy. Whether you have to switch up your footwear to keep yourself from spiraling out during a dinner rush or cough up cash to see a therapist to help you navigate a dark time, moving through grief will change you. With Kübler-Ross’ five stages to guide the way, hopefully we can all succumb to our own manners of moving forward. Take your time with your hardships: wear the boots, hide the clogs in your closet, grit your teeth as you try every avenue of possible pain evasion. It’s all a part of the process. You’ll be comfortable in good time.

Join the discussion

0 comments