“I had no idea how much I missed it. I asked the conductor after the concert if I could come back and play again. All he said was, ‘Yes, see you Monday.’”

Soteldo treated his re-entry into the conservatory with an awakened level of commitment and loyalty. He traveled to different cities in Venezuela to learn from other teachers, toured all over the world with his orchestra, and continued to grow as a musician.

“Playing in the orchestra for me was fucking amazing. It’s a sensation that, to be honest, I still don't feel anywhere else.”

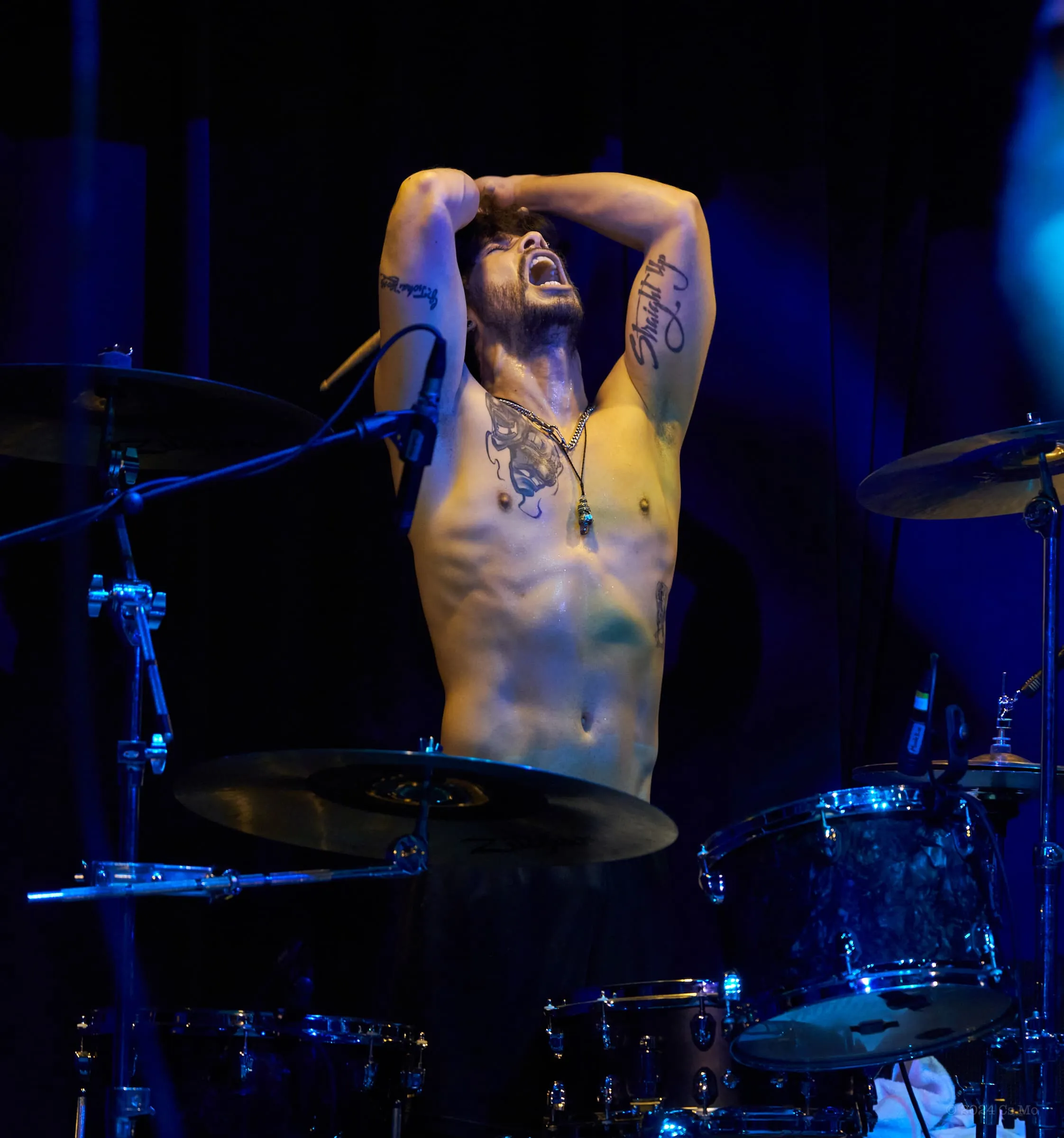

Classical music, alone, could only carry the teenager’s attention for so long, however. At 16-years-old, Soteldo witnessed a rock concert for the first time, and consequently, was introduced to a drum set and a drummer. Suddenly, a lead singer held more appeal than a conductor, a crowd of screaming people held more appeal than a theater of seated listeners, and most importantly, a single drummer held more appeal than a group of percussionists. Band members with tattoos, cigarettes and sunglasses had Soteldo rethinking how much he liked his composed, proper, performance persona.

“I saw the rock and roll life with guys being badass and hardcore. It felt so different than Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Mahler, all this music I had been playing for so long and learning. I thought, ‘This is my thing. This is what I want.’”

After that first concert, Soteldo’s mind was made up: he would do whatever it took to become a drummer. While continuing to play and study at the conservatory, he began practicing on drum sets, soaking in everything he could from shows playing anywhere near him, and even became the groupie of a rock band so that he could get into concert venues.

“I couldn’t get into bars and clubs because of my age, but as a part of a band, they never asked me for my ID.”

that, to be honest,

anywhere else.”

Eventually, he gained the courage to ask to play a song live during a show. He picked “Basket Case” by Green Day to perform, not knowing what a single one of the English words meant. In the span of a year, he transitioned from a classical musician and percussionist to a punk rock and drums addict. He had known that music would be his life, but now he knew exactly the style of music he wanted to wrap his life around. He began playing the drums more, swallowing the nerves of learning a new skill for the sake of following what he knew was his passion.

“At some point you just have to be yourself. Whatever the fuck happens next, it happens. I remember the feeling of playing for the first time: There's no turning back.”

At 18, he went to university to study percussion and became a part of a few bands. He began to see the split between percussion and drumming, two music styles that from the naked eye, seem very alike. After years of being one member in a group of percussionists, he could now be all players at once, and he loved the autonomy. With time and practice, Soteldo began finding his own sound.

“As a drummer, I can do whatever I want. I like to play very hard. A lot of people hate it and a lot of people like it, but that's how I play. And I cannot play like that in an orchestra.”

After completing school, Soteldo came to understand that the life he wanted – playing in shows, advancing as a drummer, taking care of himself and his loved ones – was only possible outside Venezuela. After applying to various schools and programs, the University of Illinois offered him a full ride to their music program on the condition that after graduating he would head up the percussion department. He’d spent his life both learning and teaching music as a means of staying out of trouble and strengthening his skills, but that chapter needed to end. Soteldo turned the scholarship down and headed in a different direction.

“I'm going to New York City, because I'm going to get in a band, because that's what I'm meant to do.”

The 25-year-old left his home country and moved to Manhattan with little more than a “Hello” and “Goodbye” English vocabulary repertoire. He got a night shift job at a 24-hour deli, threw his name and music background onto Craig’s List, and started studying English and graphic design at a school in New Jersey. By this point, Soteldo had proven to himself his ability to set goals and reach them. He was determined to fulfill the reason he came to New York.

For the next seven years, Soteldo remained in relentless pursuit of finding the right group of people to play with. People who shared his energy, sound, and drive he saw in himself. He moved in and out of several bands, sometimes choosing to leave because they weren’t focused enough or didn’t reflect his priorities, sometimes having to leave because of a breakup. As he experienced surges and dry spells of opportunities to play, he made sure he progressed as a new New Yorker, as well. He began working as a restaurant’s dishwasher, and within two years, moved up through positions to a manager. His English skills improved through constantly speaking with customers and drumming in bands.

Even though the drummer hadn’t found the perfect musical fit, he was meeting other musicians and developing not only his classical, punk rock personal brand, but also his standards when it came to what he played and who he played it with.

“The question I ask myself is always the same: Will playing this make me feel things? Because if it will, then I'm all in. But if it doesn't, I will be honest with you, I’m out. I don't give a fuck about the money or anything when it comes to me drumming or making any percussion. If it makes me feel good, I will fucking go for it. Fuck it. I don't care. What’s the worst thing that could happen?”

Soteldo’s restaurant managerial position came to demand too much of his time, taking him away from music. He needed to find a place where he didn’t have to bring the job home with him and could quickly get shifts covered when he booked a show. After trying out a handful of different places, he found Sea Wolf, a seafood restaurant in Bushwick specializing in locally sourced land and sea ingredients. Supported and understood by his managers, Soteldo has now worked there for three years, waiting tables and bartending on the days he doesn’t have a musical priority.

York City, because I'm

going to get in a band,

I'm meant to do.”

Two years ago, one of Soteldo’s former bandmates from Outernational – a group Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers used to jam with – reached out to him about a Canadian-based band new to the city, called The Dreadnoughts. The lead singer had moved to New York for a collegiate philosophy job and wanted to create an American version of his band so he could keep playing while teaching. He was wrapping up auditions but still looking for the right drummer. The first thing Soteldo learned about The Dreadnoughts was that they’re a polka band, with punk rock and sea shanty influences.

“I thought, ‘Fuck, polka? What are we talking about?’ The last time I played polka, it was with the orchestra.”

Soteldo had his suspicions of how the band would feel to him, but attended a rehearsal just to see. The Dreadnoughts has six members – lead singer and guitar, bass guitar, accordion, violin, mandolin, and drums. Within an hour of playing, Soteldo was transported back to his conservatory days with multiple instruments and harmonies. The band immediately spoke to his adult love of punk rock and his childhood love of classical.

“I was like, ‘What the fuck is this? This is fucking awesome. I am all in. I hope they like me. Please like me. I think that this is my new shit.’”

The band hadn’t just given Soteldo a chance to be a part of a strong, steady group with a sound leader. It also showed him he didn’t have to choose between being a percussionist or drummer. Both sides of himself could jam out happily. He joined the group after that rehearsal and has been playing with them ever since.

“This band is fucking punk rock and hardcore. It has polka vibes and beautiful harmonies, and gets people excited and jumping around. It’s happiness all the way.”

He still remembers the first time he joined The Dreadnoughts in front of a live audience. He wanted to be as much in the crowd’s mosh pit as he wanted to be on stage playing. He wanted to be everywhere, as long as this band was close by.

“The place was packed. We couldn't even breathe; there was not enough oxygen. It was just insane.”

Soteldo feels closer now to his bandmates and their voice than ever before. Their upcoming album, Polka Pit, features an instrumental song dedicated to one of his Venezuelan heroes, Neomar Lander, a protestor who passed away while fighting for better government policies. He sees the group as a family, with the lead singer – the philosophy professor – as their father figure, everyone calls him “Dad.”

“All of us have so much respect for him: as a musician, parent, and person in general. He's a fucking punk rocker, dude. I hope I am at least 20% of who he is when I grow up.”

For much of Soteldo’s life, he has seen a contrast between his experiences and his dreams. After years of following his gut and consistently surrounding himself with people and projects that genuinely spoke to him, he now connects areas of his life he always thought were separate. He always viewed percussion and drums as different musical entities, and now, in The Dreadnoughts, he plays both. He always saw himself wanting to be in a band over wanting to be in an orchestra, and now, he’s achieved the feeling of both. His American experience and Venezuelan roots have connected through creating his band’s upcoming album. He has, time and time again, taken risks to ensure he was following his dreams. He’s a part of a life that embodies everything he’s ever cared for.

“I've been waiting for so long to be part of something like this. I'm doing what I thought I was going to do in the future: play in a band, do shows, and be myself. This is what I do, this is who I am. This is what's up. This is my happiness.” ∎

Join the discussion

0 comments